Photography courtesy of Lowell Washburn, all rights reserved.

“. . . there was nothing to see but prairie, green stretches of grassland rolling quietly outward till lost in the haze that trembled on the horizon.” – Norwegian immigrant Laurence Larson describing his l870’s arrival in Winnebago County.

THOMPSON– Even by rural Iowa standards, Winnebago County’s Linden Township Cemetery is a quiet place. Although bordered by a well-traveled blacktop, few people seem to notice. Fewer yet bother to stop. Unless you happen to have kin buried here, there would be little reason to visit this “pleasantly forgettable” hilltop.

That’s unfortunate. Linden Cemetery is anything but forgettable. Located just southeast of Thompson, the site harbors unique artifacts of Iowa’s pioneer heritage. Home to a tilted collection of time weathered headstones, Linden Cemetery marks the final resting place for some of North Iowa’s earliest settlers. Supporting a two acre remnant of virgin prairie; the plot also offers a glimpse of a vanished ecosystem that once encompassed over 30 million acres of present day Iowa. Native prairie has become our rarest commodity; less than 6,000 acres remain statewide.

Historically, grazing by elk and bison, along with the flames of wind driven prairie fires, protected Iowa’s vast grasslands from the encroachment of trees and shrubs. In more recent times, woody vegetation has been held in check [at Linden Township] by the whirring lawnmower blades of community service minded local Boy Scouts. Care efforts intensified in 2005 when Matt Polsdofer chose the cemetery as an Eagle Scout Project. Continued preservation has currently been entrusted to the County Conservation Board.

Although cemetery prairie plants have successfully dodged the plow for the past 150 years or so, they also face new threats as a second wave of European invaders; ragweed, cucumber, brome and others seek to outcompete native vegetation. In spite of the ongoing menace, more than enough prairie species remain – leadplant, bed straw, coneflower, Indian grass, bluestem and more – to give the area historic significance.

No one is certain exactly how many pioneer homesteaders are buried here. Lettering on some of the weathered markers has become illegible. Other markers have undoubtedly vanished. Although all are interesting, perhaps none is more so than a tall headstone standing more or less in the center of the cemetery. The weathered inscription simply reads: James S. Sperring: Feb. 24, 1894 – Apr. 28, 1896.

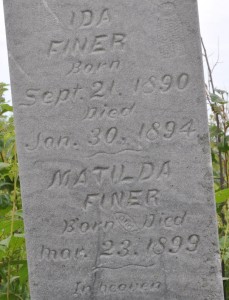

Time has long forgotten whatever misfortune befell 2-year-old James Sperring. He may have fallen from a wagon, been kicked by a horse, or simply scratched by a rusty nail. Maybe he just caught cold. Life was tough on the Iowa frontier; many settlers perished from ailments that would seem insignificant today. A large percentage of the markers scattered here — as well as in other prairie cemeteries — mark the passing of young people. A headstone for the Finer sisters provides an all too common example. Ida Finer died in 1894 at the age of 2 ½. Five years later her sister, Matilda was born and died on the same day. Buried in the same plot, their two word epitaph reads: In Heaven.

A person can’t help but wonder what people looked like or what comprised a “typical day” during the brief time that James Sperring lived here; or how the Iowa landscape appeared in the spring of 1896when, dressed in black suits and long dresses, sad faced mourners arrived by horse and buggy to comfort the grieving Sperring family. Although much of Iowa’s early history has been lost; enough has been recorded to spark our imaginations. Here is what we know.

Although dominated by a seemingly endless expanse of treeless grassland, Northern Iowa also contained an abundance of surface water in the form of countless prairie potholes, cattail marsh and shallow lakes. Original home to Winnebago and Sioux Indians the region was so wet, so pockmarked by wetlands, that European homesteaders simply avoided the area until late in the state’s development.

According to archived public record, the first party of whites to enter Winnebago County was led by Leander Farlow, who arrived in 1853 to hunt and trap. The first prairie sod was turned just two years later by homesteader Thomas Bearse. [Imagine what Bearse would think if he could see today’s farmland, machinery, and yields.] Like all homesteaders, Bearse was also a hunter who, near the boundary of present day Pilot Knob State Park, encountered and killed a large black bear.

Without exception, all early settlers had immigrated to Winnebago County from Norway. During 1857, the pioneers reported their first marriage, birth, and death. Winnebago County’s first schoolhouse opened in 1858.

By 1860, the countryside was rapidly becoming checkered with small crop fields. But insects, weather, fire and wildlife made farming a highly challenging proposition. A notable example came in 1862 when unfathomable hordes of prairie chickens assembled near the southern edge of Forest City to feed on ripening fields of buckwheat.

David Secor operated the town’s general store where homesteaders were vital customers. Upon hearing of his patrons’ plight, he determined to aid in the defense of the crop while, at the same time, to hopefully gather a few wild chickens for the pot.

Secor admitted [in a written account] that he was “never much of hunter.” Nevertheless, he borrowed a scattergun from the store’s inventory and arrived at the buckwheat fields an hour before sunset. Prairie chickens were already sailing in as Secor hurriedly began loading his double barreled, muzzleloading shotgun. Unfortunately, he forgot to pour gunpowder into the barrels before tamping down the shot and wadding.

With sunset fast approaching, the flight suddenly gained momentum as increasing numbers of hungry prairie chickens began fogging the field. Now in a panic, Secor had no easy means of clearing the obstructed barrels. By the time he eventually cleared the first tube, the sun was at the horizon. With no time to waste, he decided to go with the single barrel. Although many of his shots were misses, Secor somehow managed to bag 19 plump chickens before darkness closed in — an admirable tally for a “citified store keep” who did not regard himself as a hunter.

Iowa’s pioneer farm economy was richly diverse. In addition to producing pork, poultry and beef, farmers also planted more than a dozen crops including wheat, flax, oats and barley. Then as now, national politics provided a popular topic for cracker barrel discussions. Historians noted that Winnebago was “always a strong Republican county”; a fact borne out during the 1864 presidential election where a strong turnout of eligible [white male] voters cast 39 votes for Lincoln but just 13 for McClellan.

Civilization swept across Northern Iowa at a breakneck pace. In 1860, there were only 168 Norwegian immigrants in the entire county. Within ten years, the number of whites had nearly tripled to 1,562. By 1900, the population had risen to around 13,000 [10,500 live in Winnebago County today] with nearly two thirds of those early residents living on farms. Prairie fires were no longer a threat. Elk, bison, deer, wolves, passenger pigeons, and cranes had vanished. Nesting Canada geese and prairie chickens would soon follow.

Standing among the weathered headstones of Linden Cemetery, it is fun to imagine what daily life and the countryside must have looked like when young James Sperring played among prairie grasses. Fun, yes. But also impossible.

LW

Thanks to Winnebago County Conservation Board Director, Robert Schwartz for his assistance in researching this column.

PHOTOS:

1– Entrance to Linden Township Cemetery

2 & 3 – Link to N. Iowa’s prairie heritage; James Sperring and other pioneer headstones.

4 – Iowa Prairie; a vanished ecosystem that once covered over thirty million acres of present day Iowa. Less than 6,000 acres remain today.

5 – A bumblebee gathers pollen from wild purple prairie clover at the Linden Twnshp. Cemetery.

6 – Greater prairie chicken – a bird once so abundant that it threatened Iowa cropland.

7 – A female dickcissel brings a hopper to its young in Winnebago County.

______________________________________________________________

Susan Judkins Josten

Susan Judkins Josten Rudi Roeslein

Rudi Roeslein Elyssa McFarland

Elyssa McFarland Mark Langgin

Mark Langgin Adam Janke

Adam Janke Joe Henry

Joe Henry Sue Wilkinson

Sue Wilkinson Tom Cope

Tom Cope Kristin Ashenbrenner

Kristin Ashenbrenner Joe Wilkinson

Joe Wilkinson Dr. Tammy Mildenstein

Dr. Tammy Mildenstein Sean McMahon

Sean McMahon