Photography courtesy of Lowell Washburn, all rights reserved.

To say that I’m not much of a techie would be something of an understatement. I grew up in a world that is now mostly vanished. When I began writing, high tech meant a good ink pen and a clean sheet of paper. Wildlife photography consisted of scrolling an expensive roll of film into the back of a camera body and then waiting for days to see the results. Telephones were something that hung on the wall, music was played on rotating turntables, and I can still remember our family’s first black & white television.

Times have changed. Today we are living in the age of computerized cell phones, digital television, digital photography; digital everything. The list of push button devices designed to provide humankind with instant gratification seems endless. When it comes to the many advances the Electronic Age has provided, I’ll admit to not really understanding very much of it; and to displaying a thorough dislike for a lot of it. Most of the time, I feel like the latest roadkill on the Information Highway.

Having said that, I also freely admit that the Computer Age has greatly advanced our knowledge and understanding of almost everything – including the natural world. My latest example came at the end of August when I received an email from my good friend Bruce Rich who was in Los Angles, California.

But before I get into Bruce’s message, let me set the stage by going back to the previous evening which was August 28. The weather was beautiful. The night skies were crystal clear, the breeze fresh and cool, and the bright and growing ‘blue supermoon’ – the next of its kind won’t be seen until Jan. 2037 –was nearly full. If ever the conditions were set for a dramatic nighttime migration of warblers [and other birdlife] tonight would be it.

The night passed and, with camera in hand, I set out early the next morning to see if the hoped for migrants had arrived. Amazingly, I spotted my first bird before even clearing the house – a little, black capped Wilson’s warbler sitting atop my backyard air conditioner. The Wilson’s was a precursor of good things to come. Moving to more traditional woodland habitats, I soon spotted a beautiful pair of Magnolia warblers, followed by American redstarts, Nashville warblers, Myrtle warblers, a black-throated green warbler, chestnut-sided warblers, black-and-white warblers, a single oven bird, and a split-second flash of what I thought to be a Canada warbler. Warblers were so abundant that, on more than one occasion, I could simultaneously see more than one species through the camera’s viewfinder. But the morning’s real highlight came with the sighting of several energetic and colorful Blackburnian warblers – a rare species for me. Flashing in and out of thick cover, I couldn’t get an accurate count on them, although I can say with certainty that there were more Blackburnians than I have ever seen in a single day. In addition to warblers, there were other woodland migrants including buntings, orioles, grosbeaks, vireos, and others.

By the time the morning ended, it had become abundantly clear that previous clues pointing to a classical migration had indeed held water. The combination of clear skies, cooling breeze, and nearly full moon had delivered a major invasion of songbirds. As always happens during such events, I marveled at the ability of these tiny travelers to unerringly navigate across hundreds of miles of trackless sky. And as also happens during such events, I couldn’t help but wonder how many birds had passed overhead during those nighttime hours.

It was not until I returned to my desk later in the day that I discovered Bruce Rich’s email – the one I mentioned earlier in this column. In essence, Buce’s message directed me to an internet link to the Cornell Bird Lab, and to one of its many features called the Bird Cast Migration Dashboard – something I had never seen before. Opening the link, I was immediately blown away.

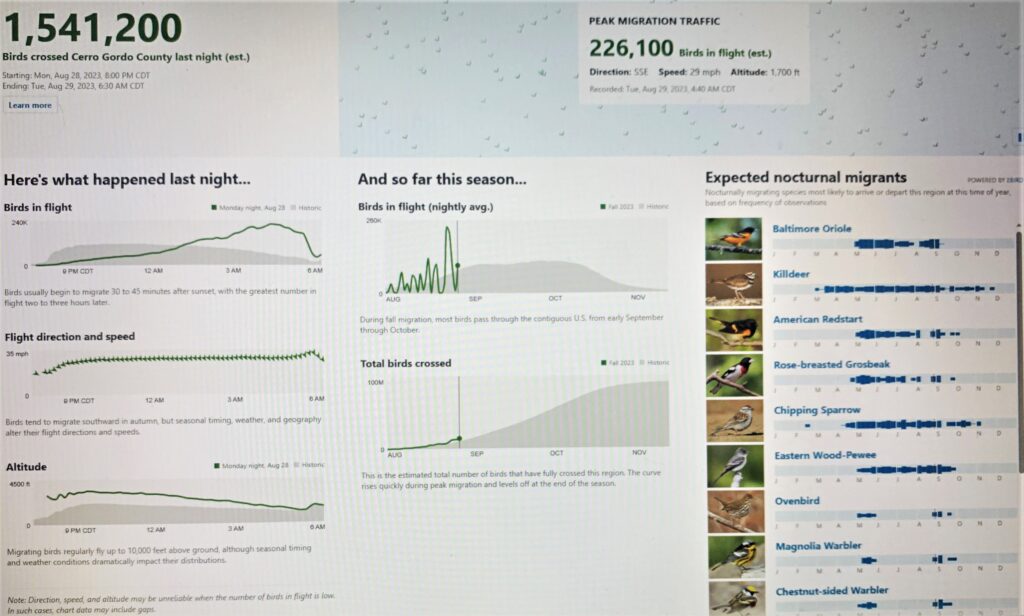

A networking product of the U.S. Geological Survey, the National Science Foundation, NOAA, the National Fish & Wildlife Foundation, and others, the Bird Cast Migration Dashboard utilizes, “cloud-based computing, big data analytics and radar ornithology” to generate real time information on when, where, and how many birds are traveling during any given migration within the continental U.S. Migration information can be as broad, or as concise, as you choose to make it.

The data Bruce sent me was concise. Remember when I said that I couldn’t help but wonder how many birds had traveled overhead during those nighttime hours of August 28? Well – here’s the amazing answer to that question.

According to the Migration Dashboard, a total of 1,541,200 birds traveled across Cerro Gordo County, Iowa [where I live] during the moonlit night of August 28, 2023. That’s not all. Most of those birds were migrating at an average speed of around 30 mph, and most were moving in a south southeasterly direction. The migrators were flying at an average altitude of 1,700 feet, with a peak number of birds [226,100] detected between the hours of 4 am and 5 am. By sunrise, most birds had descended back to earth to feed and rest during the daylight hours.

As I continued to navigate this amazing product of modern techknowledgy, I was suddenly struck with the idea that Bruce Rich – while sitting 1,800 miles away and on the far side of the Rocky Mountains – was aware of more of the details concerning last night’s migration over northern Iowa than I was; and I was actually sitting in the woods viewing and photographing the very birds he was telling me about. Once again, modern-day Electronic Age techknowledgy had flexed its mighty muscle, releasing a myriad of untold information regarding the previously secret lives of wild birds. For a guy that barely knows how to run a screwdriver, it was a humbling moment.

I could go on, but I’ll leave it with this. If you’re someone who is interested in science, birdlife, computer techknowledgy, weather – or maybe all these things — then you defiantly need to visit the Cornell Bird Lab’s Migration Dashboard. It will blow you away.

Susan Judkins Josten

Susan Judkins Josten Rudi Roeslein

Rudi Roeslein Elyssa McFarland

Elyssa McFarland Mark Langgin

Mark Langgin Adam Janke

Adam Janke Joe Henry

Joe Henry Sue Wilkinson

Sue Wilkinson Tom Cope

Tom Cope Kristin Ashenbrenner

Kristin Ashenbrenner Joe Wilkinson

Joe Wilkinson Dr. Tammy Mildenstein

Dr. Tammy Mildenstein Sean McMahon

Sean McMahon