Photography courtesy of Lowell Washburn, all rights reserved.

Sometimes The Greatest Treasures Are Found In The Most Unlikely Places

It was late fall, 1981. The skies were dark and ominous, and there was a distinct feel of winter in the North Iowa air. Gusting autumn winds made it feel even colder. In other words, it was the kind of day that every duck hunter dreams of.

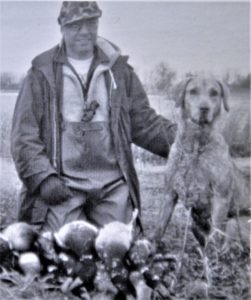

Following morning services, Carol and I had invited my folks up to the farmstead for Sunday dinner. Once the meal was finished, Dad and I quickly decided that — in spite of having put on a full gorge — that a midday duck hunt sounded more exciting than an afternoon nap. Sandy, my Chesapeake Bay Retriever, eagerly accepted an invitation to join the outing. Throwing a couple of bags of decoys into the back of my truck, we headed for Cerro Gordo County’s Mallard Marsh, located a mile to the east.

We had decided to hunt the area’s North Pond which is located on the eastern half of the mile long marsh. Donning chest waders and slinging the decoys over our backs, we began marching toward the pond — our pace noticeably quickened by the fact that flocks of ducks could already be seen working low over the marsh.

Arriving at the pond’s shoreline, we emptied the decoy bags and loaded our shotguns. We were still setting up our blind when the first flock of mallards appeared from the north. As always, Dad was carrying his vintage 1930s, brass-belled duck call. I was blowing a Fernandez highball call, and we lost no time in sending up a duel greeting to the oncoming birds. Laboring into the wind, the ducks heard our calls, spotted the decoys, and set their wings. Obvious migrants, the ‘new birds’ dropped into the spread as tame as teal. From there, it was game on as we enjoyed a half hour of virtual nonstop action involving flocks of mallards, pintail, wigeon and gadwall. Then, as suddenly as it had begun, the flight shut off. Pouring a hot cup from the thermos, it was the first time we’d had an opportunity to visit.

I don’t remember how many ducks we’d bagged, but I do know it was enough to make us chatter like a couple of excited third graders. Even Sandy was dancing for joy. I don’t remember what led the talk in that direction, but our conversation eventually turned to the subject of waterfowl bands – those numbered aluminum rings that, when placed on the legs of wild ducks and geese, enable biologists to track migration routes, gauge mortality, and make intelligent management decisions. Back then, bagging a banded duck was much rarer than it is today. Nevertheless, I had managed to acquire a collection of four or five duck bands which I had attached to the lanyard of my call. Despite having hunted ducks since sometime in the late 1930s, Dad had yet to bag a banded bird.

“You know, after all these years I’ve never shot a single banded duck,” he lamented.

Before I could comment, our conversation was abruptly terminated by the appearance of an approaching group of mallards. Circling the decoys, the birds decided to pile in on the third or fourth pass. Dad took the first shot which upended a fat, full color Greenhead. I can’t exactly recall the results of our following shots as the startled fowl flared back into the wind and were gone.

Sandy sped off to retrieve the first bird to hit the water, which was that colorful drake mallard. Gently grasping the plump bird in her mouth, the dog turned and headed back for the blind. The duck was being carried belly-up and, and as the Chesapeake drew near, I could clearly see a silvery ring on the drake’s bright orange leg. They say that timing is everything, and in this case it was.

“Hey Dad, did you just say that you’ve never bagged a banded duck,” I asked.

“Yes; why do you ask,” he replied with a somewhat quizzical expression.

“Well, because you have now,” I laughed.

Sandy had arrived at the blind now, and we celebrated Dad’s first ever banded duck! We eventually learned that the mallard had been banded the previous February as a wintering adult at Tennessee’s Bear Creek Wildlife Management Unit located to the east of the World Famous Reelfoot Lake waterfowl area. Waterfowl are amazing creatures and we pondered how many miles the bird had traveled, what he’d seen, and how many round-trip migrations he’d completed before arriving at Mallard Marsh.

Time passes quickly. Days and years come and go. But in spite of the fact that the event occurred forty years ago, the memory of that Sunday afternoon when the weather was perfect, the mallards cooperative, and Dad bagged his first banded duck has never dimmed. Even today, I frequently relive that perfect hunt in my mind’s eye.

Unfortunately, Dad’s band was somehow lost over time. Sad, but that’s the way it goes. Things get misplaced. Things vanish into thin air. That is until this week. While helping to downsize some of my mom’s personal items, I came across a small heart shaped jewelry box. Upon opening the lid, I discovered a treasure beyond price. There were no diamonds, gold, or rare coins in the box. Instead, nestled among an odd assortment of pheasant cuff links, tie clasps, a church pin, and a couple of .22 shells was a beautiful aluminum duck band. Could it be? It had to be. After logging into the Federal Bird Banding Lab, it was quickly confirmed that this was indeed the “Tennessee Bird Band” from that long ago duck hunt.

It seemed too good to be true. To me, the band represented far more than an interesting piece of waterfowling memorabilia. It was, in fact, a tangible artifact from one of my most cherished memories. Elevated to the status of a family heirloom, the mallard band now resides as the single item on the lanyard of Dad’s old-time handmade duck call. If I have my way, the two will never be separated again.

LW

Tom Cope

Tom Cope Sue Wilkinson

Sue Wilkinson Susan Judkins Josten

Susan Judkins Josten Rudi Roeslein

Rudi Roeslein Elyssa McFarland

Elyssa McFarland Mark Langgin

Mark Langgin Adam Janke

Adam Janke Joe Henry

Joe Henry Kristin Ashenbrenner

Kristin Ashenbrenner Joe Wilkinson

Joe Wilkinson Dr. Tammy Mildenstein

Dr. Tammy Mildenstein Sean McMahon

Sean McMahon