Photography courtesy of Lowell Washburn, all rights reserved.

Pike’s Peak is one of Iowa’s best known state parks. Offering clean campgrounds, spectacular views of the Mississippi River, and an interlinking maze of beautiful woodland hiking trails; Pike’s Peak has something for everyone. Last week, Carol and I decided to take advantage of the abnormally cool July weather and explore the park’s trail system. The Myotis Trail was first on our list. Although far from crowded, it was obvious that a number of other folks had had the same idea. The hike was going well until I heard a piercing, human shriek from over the hill. Moments later, two twenties-something female hikers came bursting into view. No longer using the trail, the girls were now headed cross country — making a direct beeline for the area’s parking lot/concession area.

“What’s going on?,” I hollered as they angled past.

“Snake!,” one of breathless hikers exclaimed.

“What kind?”, I queried.

“A big black one; and I almost stepped on it,” she replied.

“Where?”

“Back on the trail,” she responded; pointing a thumb back over her shoulder.

Hustling to the site, we quickly discovered the cause of the ruckus — a magnificent, 53-inch, black rat snake lying smack in the middle of the hiking trail. One of Iowa’s larger snake species, the black rat snake is a common inhabitant of the Mississippi River bluff country. As its name implies, the rat snake is a rodent catching machine. One of the few snakes that prefers living in the darkest center of the deepest woods, rat snakes rely on their dark coloring to keep them invisible as they wait in ambush for passing rodents such as white-footed mice or chipmunks. Rat snakes can also take to the trees and are superb climbers. The majority of Pike’s Peak State Park is covered by forest and loaded with chipmunks, making it ideal rat snake habitat.

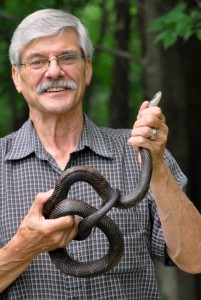

When approached by humans, or other potential threats, rat snakes tend to remain motionless; hoping to go undetected until the danger passes. This snake was no exception, and I suspect that it hadn’t moved an inch until the aforementioned hikers had nearly put a foot on it. Determining that the center of the park’s most heavily used trail was probably not the safest spot for the snake, I decided to relocate the herpitile into nearby cover. Gently placing my boot on the snake’s back, it arched its neck and delivered an authoritative bite to the top of my foot. Clasping the reptile with both hands, I lifted it from the ground. Soft and velvety to the touch, the snake had just shed its skin.

Hearing a noise, I looked to the right and spotted another group of hikers approaching from uphill. “What have you got?” one of them asked. I told them, and they hurried over for a look. Now it’s been awhile since I’ve conducted an outdoor classroom, but I was suddenly back in business. News of the snake spread, and I hung around for awhile as park goers received what was apparently their first nose to nose encounter with a large reptile of any species. After everyone had gotten a good look, I obtained a couple of “voucher photos” and then released the snake into a nearby patch of wild ginger. The animal disappeared into the dense foliage and we continued our hike. I’m happy to report that all human hikers and park reptiles have been safely returned to their native habitats.

Rat Snake Trivia: Black rat snakes commonly share winter [hibernation] dens with timber rattlesnakes. Early folklore had it that the rat snake actually guided the rattlers to their wintering areas which led to the species’ receiving the common name — ‘black pilot snake’.

Susan Judkins Josten

Susan Judkins Josten Rudi Roeslein

Rudi Roeslein Elyssa McFarland

Elyssa McFarland Mark Langgin

Mark Langgin Adam Janke

Adam Janke Joe Henry

Joe Henry Sue Wilkinson

Sue Wilkinson Tom Cope

Tom Cope Kristin Ashenbrenner

Kristin Ashenbrenner Joe Wilkinson

Joe Wilkinson Dr. Tammy Mildenstein

Dr. Tammy Mildenstein Sean McMahon

Sean McMahon